Today, we will go through the differences between VM’s and Containers, and what problems Docker is meant to solve.

Virtual Machine (VM) vs Containers

Virtual Machines

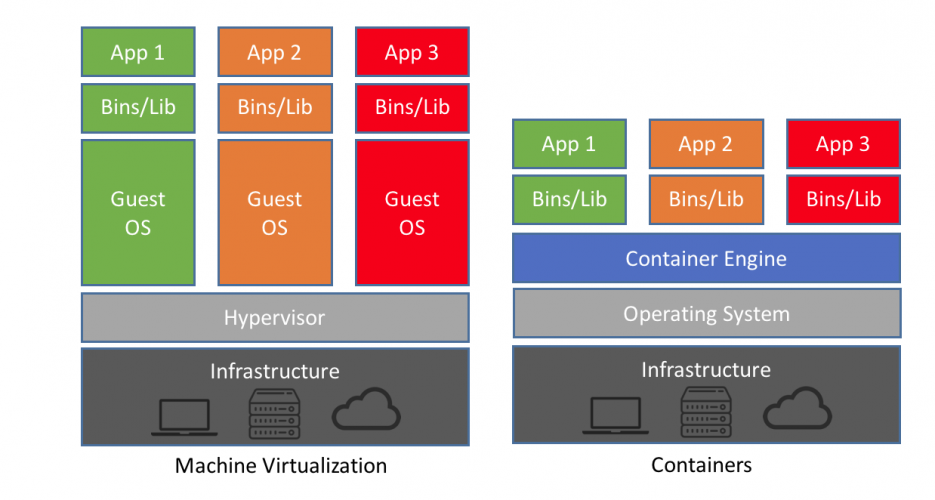

What is a VM? A VM provides the functionality of a physical machine, and provides you with the ability to run entire operating systems virtually. However, it is an isolated segment of a physical machine that requires either special hardware or software to run and allocate resources.

- Hypervisor: Manages the execution of guest operating systems the VMs run. There are 2 types of Hypervisor

- Type-1: Bare metal - The hypervisor runs directly on the hosts hardware.

- Type-2: Hosted - The hypervisor runs on top of the host OS.

With the ability to run multiple OS’s your estate on one bit of kit, it was a revolutionary step in the field of cloud-computing. It meant companies didn’t need to run huge amounts of kit to isolate applications/teams.

You also have the ability to backup VMs via instance snapshots, which will take an image of the whole machine in it’s current state. When you redeploy from a snapshot, the OS, and binaries are restored to the point-in-time snapshot.

There is also an added layer of security. If there are questionable actions being taken against a VM, it does not effect the host (unless they have the ability to break out of the VM).

So far so good, but there have to be downsides? And there are. VMs require specialised hardware/software to run. They are hefty in size, due to the host needing to install a full OS, plus binaries on each deployed VM. This becomes an issue when you start to run out of capacity (in both private and public clouds). Which leads to the next point, that to run VMs effectively across the estate of a large corporation is expensive. Not as expensive as the equivalent amount of hardware, but still not a great solution for worldwide companies. Finally, as you might have guesses, adding another layer of abstraction has a general efficiency impact as you are not interacting directly with the underlying hardware.

Containers

Where VMs virtualise hardware, the purpose of a container is to virtualise software! Simple enough to understand. But what does this entail? Docker describes a container as:

“A container is a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another. A Docker container image is a lightweight, standalone, executable package of software that includes everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries and settings.”

This is a great explanation of what a container is and does, but what are its features?

Firstly, each container shares the host OS kernel, binaries, and libraries. All shared components are read-only, meaning they are very lightweight (only MBs, not GBs like VMs) and they are portable. Also, as they share the host OS, it drastically reduces management overhead. Their portability comes from the fact they are not bound by the hosts OS calls, they interact with container engine API. Meaning the only prerequiste to run your containers is to have a container engine installed on the host machine. It doesn’t matter where or when the container was built.

The simplest way to think about a container engine, is as a container runtime that essentially does what a hypervisor does with hardware. But instead of acting as a layer between the hardware and the host, it is a layer between the host and the applications running on that host. It allows for effective resource utilisation of that host, whilst also keeping your applications isolated.

In conclusion

This post describes a one-vs-another between VMs and containers. However, when looking at both, they shouldn’t be seen as one being inherently better than another as the solve different architectural issues. In the next post in this series, we will be delving into the architecture of Docker itself, setting up Docker locally, and running an image from DockerHub.